Probably the third or fourth thing I get asked by would-be writers—after “Where do you get your ideas?”, “Are you working on the next book? When will it be finished?”, and “I have this great idea; how about you write it and we split the money?”—is “How do I become a good writer? How did you do it?”

I’ve argued about that question with people from insurance salesmen to college professors. 99.9% of the arguments start like this:

ME: “What do you think a good writer is?”

THEM: “Somebody who writes good books.”

ME: “What is a ‘good book’?”

THEM: “What do you mean, what’s a good book? One that’s written well!”

ME: “So what does ‘well-written’ mean?”

Sometimes, I get a few examples of books the speaker considers well-written, which lets me trot out a variation on Damon Knight’s famous definition of science fiction—“It’s what we’re pointing at when we say, ‘that’s good writing.’” Sometimes, people start with examples of “rules” for good writing, like Don’t use adverbs or Never start a story with weather or Don’t use passive verbs and I shoot them down. Sooner or later, we get to this:

THEM: “Well, then, what do you think good writing is?”

ME: “Subjective.”

Almost nobody likes this answer, but it’s the only one I have. The argument generally goes on for a while, until I end up quoting Somerset Maugham at them (“There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”) and we all give up.

The difficulty, as I see it, is that the phrase “good writing” sounds as if it means something everyone agrees on, with a bunch of clear, consistent, universally applicable, objective rules. The way the term is generally used, however, is to identify 1) a book or story that the speaker really liked (as in, “You should read this book—it’s really good.”) or 2) a book or story that is considered part of the nebulous thing called “the literary canon,” meaning that it’s something that probably gets taught in a lot of English classes in high school and college for reasons.

In that usage, “good writing” or “good stories” is not a consensus, or something that has clear agreed-upon rules. For every list of “rules for good writing,” you can find much-admired and/or popular books that break every one of them…and you can find books that everyone thinks are horrible that follow most or all of those rules.

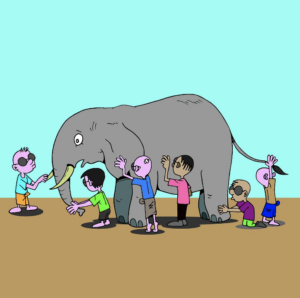

Furthermore, if you dig into lists of books published in the last two centuries, you can find many that were, when they were published, considered masterpieces, but which haven’t lasted…and quite a few that were considered cheap potboilers when they first came out, but which are now “classic literature.” Even the literary canon changes over time. Looked at objectively, it is obvious that any standards for “good writing” have changed repeatedly, and even when they’re relatively stable, people disagree. It’s a lot like the story about the six blind men who got into an argument about what an elephant was like, and couldn’t decide whether it was like a fan, a wall, a rope, etc. because they’d each got hold of a different part of it.

“Good writing standards” also differ among different cultures—and I include here both the sorts of culture that are tied to ethnicity and country-of-origin and the sorts of culture that form around and within particular genres and subgroups. A few minutes’ thought should make it obvious that in, say, Japanese (which has a completely different sentence structure from English, as well as three different writing systems with specific conventions regarding when and how they are used), “good writing” has to be very different from what people consider “good writing” in English. And there have been at least two major shakeups in what readers-in-general considered “good science fiction writing” in my lifetime, and a lot of smaller arguments over where subgenres like cyberpunk and magical realism fit on a spectrum of good/bad writing.

That doesn’t even get into some of the subtle elements that make stories uncomfortable (and therefore not “good writing”) to people from different cultures. One of the best examples is the rather long article Shakespeare in the Bush in which an anthropologist tries to explain the “universal concepts” in Hamlet to people who proceed to interpret the events according to a completely different cultural context. Another example is the differences in folk tales, where most European cultures expect things to come in threes—three wishes, three Fates, three-headed dogs—but in some other cultures, things are expected to come in fours or fives. Each type feels oddly abrupt or unfinished to readers from cultures that apply a different norm.

Also, pegging certain techniques as either “good writing” or “bad writing” begs the question of what, exactly, makes that technique “bad” or “good”? It’s been fifty years since I first noticed that certain writing choices—like first person, or omniscient viewpoint, or the use of adjectives and adverbs—were condemned in some writers, but lauded in others. It took me a while to figure out that the choice or technique wasn’t inherently good or bad (which is what the label implies); it was ill-advised application or imperfect execution of a tricky or difficult technique that was the problem (at least, in the examples I was given).

This is why I try very hard not to use labels like “good” or “bad” in this blog. (I slip up from time to time, I’m afraid.) Techniques are neutral—they have different effects on the reader, that’s all. The trouble comes when a writer picks a technique that doesn’t have the effect they’re trying for, or picks a useful technique but can’t quite pull it off. Both are issues that are correctable, if the writer recognizes them as the fundamental problem. Labeling techniques as good or bad, or even as desirable or undesirable, puts the onus on the technique (which cannot change itself), rather than the writer (who can probably change if they put their mind to it). This is not productive, to my way of thinking.

Most of the “rules” of “good” or “bad” writing, from what I can see, are really just guidelines that people have found are *likely* to please or displease *many* readers.

If you put three adverbs in every sentence, *a lot of* readers *probably* won’t like it. If you use monosyllables and an oversimplified sentence structure over and over (“See Jane. See Jane run. Run Jane run.”), you’re not *likely* to win over *a great many* readers.

So it’s not too hard to find techniques that *probably* won’t be liked by *quite a few* readers.

(Unless you’re Shakespeare or something. Genius writers can pull anything off. For *many* readers, anyway.)

How do you go from “some techniques don’t seem great” to good writing? Guess I, too, have to quote Somerset Maugham…

It occurs to me that my response is about writing craftsmanship. You know, “measure twice, cut once” is good guidance for carpenters, but some super-experienced genius can probably ignore that.

Ms. W, would an entry on art vs. craft be a worthwhile topic?

Art is process-driven and involves unrestricted creative liberty; crafts are product-driven and tend to all come out looking the same…

This comes from my early childhood education classes, so it’s a little off-topic in the current form, but I think it could be wrangled jnto a good analogy if I knew where to start. Perhaps a good point is that the techniques of craft are the same across the board, and every writer should learn them, but it’s when a writer combines their own unique artistic style to the craft techniques they’ve learned that something original and truly wonderful is born.

(Unless you’re Shakespeare or something. Genius writers can pull anything off. For *many* readers, anyway.)

I really don’t care for Shakespeare. So yeah, no definition of “good” is universal.

Sometimes being an iconoclast has its uses — I hated enough of the great classics I was subjected to in school that I decided early on the only definition of “good book” that mattered to me was my own. Of course, it’d be nice if more of the people who hand out publishing contracts agreed with me…. 😉

I like this! Much as I respect Tolkien, I don’t read LotR very often–I tend to get bogged down in his prose. Likewise, I love reading Christian fantasy novels because they align with my beliefs–but very few of them are “written well,” in that they tend to be really preachy and that’s not fun for me to read. However, I’ll read and reread 90% of Brandon Sanderson’s books because the way he writes, the prose vanishes and I can delve right into the story. Similarly, I love Shannon Hale’s Books of Bayern series because it’s not hard to tell that every sentence in those books was crafted with thought and care in order to provide the best story-reading experience possible.

In counterpoint, though, there’s a book called “Just Stab Me Now” that by many accounts has “bad writing” because the author makes use of infodumps and the prose isn’t always as smooth as it could be, but which I love because it’s an incredibly fun, well-done example of meta-story in which an author is struggling to wrangle her characters to fulfill her desired romance tropes (all of which to say, go look it up, because I enjoyed it; this is officially a book recommendation now). So I think that saying good writing is subjective is, frankly, the only decent answer to be had.

Wayne C. Booth in *The Rhetoric of Fiction* observed that many such rules reduce to “If you do this badly, it will be bad.”

Though some “masterpieces” of the day probably played too hard on the conventions. *Trent’s Last Case* — Chesterton and Dorothy Sayers both loved it, I tracked it down, and it deserved to be forgotten, but I suspect it was the way it played with detective tropes of the day that did it.

I love that quote.

In a conversation with a writer about preferred genres, I said that I liked pretty much anything that was well-written. By “well-written”, she assumed I meant florid, purple prose that never used a short word when a pretentious multisyllabic one could serve – which is the precise opposite of what I meant. That sort of affected writing was considered superior in the 18th and early 19th centuries, but now we are more likely to value lean, vigorous prose that does not call attention to itself.

Part of the problem is that nobody, not even the English teachers I had (assuming I’m remembering right after all these years) defines their criteria for “good” vs. “bad.”

Do they mean slipping in lots of literary allusions? Writing on multiple levels? Subtext that fits their values? Rhythmic sentences? What are they looking for?

Most people call anything they enjoy “good,” which is silly on the face of it. “Enjoyable” and “good” are not synonyms.

But if we don’t define our terms, our discussions become indeterminate. Everyone argues, but mostly past each other.

We have occasionally played a game of “taking your RPG character to a movie”–that is, you view the movie as much as possible in that character’s persona.

We took my Call of Cthulhu character Kristoff to _The Mummy_, and after the scene with the men devoured alive by beetles, he said in shock “In my day these were the sights that destroyed men’s minds: in your day they’re… entertainment?”

And we took Vikki, who was raised by aliens, to the live-action _The Grinch_, and afterwards asked her to summarize the plot. She said, it’s a gripping power struggle between Cindy Lou Who and the Mayor, with the Grinch as a wild-card Cindy hopes to manipulate. She laid this out in some detail and it all made sense….

In the second case, Vikki thought it was a good movie and I did *not*. So that ties in to the theme of this post: it’s extremely, extremely subjective!