Once you’ve committed to the seed-crystal idea you’re going to turn into your first novel, you’ll have to develop it. (The commitment part is important. There will be some point—possibly more than one—in this process where everything you’ve written sounds stupid, clichéd, or just too frustrating to work with, and you’re going to want to give up. If you really mean it when you say “I want to write a novel,” you will have to get through this point (possibly more than once). Stubbornness is one of the cardinal virtues for writers, but being prepared for this to happen helps, too.)

Ahem. So, developing the idea, frequently referred to as “prewriting.”

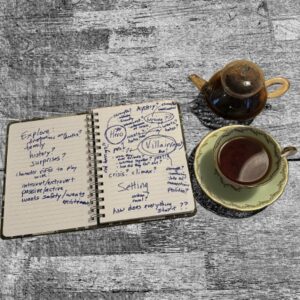

“Prewriting” is, in essence, everything a writer does before they actually sit down to work on the story. It’s a fuzzy term, because “what a writer does before starting to write the story” ranges from finding a pen, a notebook, and a comfy place to work, to 500 pages of meticulously researched and organized notes on characters, geography, history, politics, plot arcs, and whatever else occurs to them. In other words, what prewriting is, how much of it one does, and how long it takes, varies from writer to writer and from book to book.

This makes a lot of the available advice on prewriting a bit problematic for first-time authors, because first-timers usually have no idea how they write, or what sort of prewriting will work for them. Also, prewriting is really easy to overdo, (especially for pantsers, though anyone can have this problem). “Overdoing it” means making up so much in advance that the story grinds to a complete halt because there is no elbow room for adapting on the fly during the actual draft. Overdoing can also mean getting so lost in the research that you never get around to actually writing the story. Setting hard time limits on research can help avoid doing 30 years of research in order to avoid ever starting to write a novel.

Overdoing prewriting and/or research can be related to specific parts of an upcoming novel. That is, one writer may need six months of research and 200 pages of notes on the lives of the upper crust in London in 1817 in order to feel comfortable starting their story, but having more than a one-sentence description of each of their major characters makes them feel as if their cool idea is suddenly waist-deep in glue.

Trust your intuition. If it feels as if you need to know more about the political plotting, make up or research more; if you feel as if a page or two of generalities is enough, stop there. Also, unless you are one of those writers whose writing sets up like quick concrete, remember that you can always change anything that hasn’t actually been mentioned in the story yet (and you can change it in the story if you’re willing and able to revise—having a better idea is always a Good Thing).

The purpose of prewriting is to make it easier to write the story, keep it consistent, and make it realistic. The consistency and realism parts can often be done after the first draft is complete, if you are okay with however much revising and rewriting you need, so the key to effective prewriting is, “What do I need to know right now to make writing this story easier?”

Most prewriting tends to focus on one or more of the Big Three—setting, characters, and plot. The idea is to take your seed-crystal idea-trigger and develop it as much as you need to in order to get started. If your trigger idea is the first scene, your prewriting may involve writing a sketch draft of that scene (i.e., a bare-minimum sketchy zeroth draft of the key dialog/setting/action points that are the core of your idea), and then pausing to flesh out your “prewriting” notes on the culture, politics, history, geography, characters, backstory, plot, possible subplots, and so on.

Since I write fantasy, I’m frequently making up different cultures, and one of the prewriting things I have learned to do is to make up a short list—maybe half-a-dozen—culture-specific names, so that if I need a minor character, I can just grab a name off my list instead of either stopping to think of one, or calling the character “X” or “xxFred” and making something up later. On the other hand, I’m not above suddenly inventing an impassable mountain range in the middle of Chapter 13 in order to keep my characters from heading off in that direction, even if those mountains were nowhere on the original map I did during my prewriting.

Similarly, I’ve never found it useful to do much prewriting/inventing of my characters—a few plot-relevant details of their life histories and/or a quick summary of how-they-got-into-this-mess is about the extent of it. I have to write my way into their personalities. I do need a bunch of background/worldbuilding, and often some idea of the history and politics; I also need a clear idea of the plot (though I never, ever end up sticking to it in specifics, even if the ending still has the same good guys winning). But that’s me. Every writer is different.

So basically, prewriting involves sitting down and thinking about the Big Three and making some notes (as few as a bullet-point list of five things you don’t want to forget to put in the story, or as many as 500 pages about the history, culture, character backgrounds, and plot outline) that you think will be helpful when it comes to the story. You are not required to stick to these notes—as I mentioned, I don’t; for me, they are a sort of mental safety net. Having them reassures me that I know what I’m doing, and also gives my backbrain something to rebel against.

Finally, “prewriting” is not the only time you spend making stuff up and/or researching. These things can and do get done later in the process, when there is enough book written that the writer has a clearer idea of what else they need to know. There can also come a point at which the writer simply cannot stand not writing the actual draft for one minute more. At that point, it doesn’t matter whether there is “enough” prewriting. It’s time to start Chapter One.

My first few stabs at writing a novel all foundered, and deservedly so. An opening scene and an idea of a world weren’t enough for me, I needed to know more.

Once I figured out what I needed to start with, *then* stubbornness came to my aid. 🙂

Current project is stuck because I don’t know enough about the space station to generate events there. So my characters sit and chat, nervously, because they are sure something is going to happen….

I am digging into its history in the hopes of understanding its current situation better. Must have been a science outpost before they realized the swarm were intelligent and spacefaring, but run by the military now: the scientists probably don’t appreciate that. This is leading into wondering what a newly discovered Terrestrial world is good for, economically. Not mining, I wouldn’t think. Useful biologicals are a long-term project but can’t be exploited immediately.

The scientist/military tension is a bit cliche, on the other hand it’s hard to see how there wouldn’t be. One could add a third prong which is commercial interests, but they’d need to see some profit opportunity. Multiple Terrestrial worlds are known by this point: what makes this one appear valuable?

This is not as much fun as my characters chatting, but if I don’t crack it, nothing will ever happen. I know that Ryan’s immediate superior is concealing the fact that his son is a telepath like Ryan: which makes him sympathetic, but also makes him refuse to ever see Ryan face to face (for fear Ryan will find out), and leaves him very susceptible to blackmail if anyone finds out. But that’s not yet a conflict, just a seed.

It took me some time to learn that I needed to jot down the sequence of scenes that would get to a resolution in order to compel the story to not peter out.

And decades later, I learned that some needed me to use some kind of plot skeleton to ensure that the story took some sharp turns in the middle.

I do very little pre-writing, at least on a conscious level. (One has to assume my subconscious mind is doing quite a lot of it, or else is extremely fast at making things up on the spur of the moment.)

Mid-writing, now…. It’s not at all uncommon for me to stop somewhere in the middle of a book and sort out all the things that have to come together for the ending to work, and oh hey don’t forget this bit, which is necessary for the sub-plot or just cool and fun, and be sure to name-check that bit of backstory again to support why the MC makes the choice they do later.

I came up with a story-concept recently (not a plot, just a concept), and as an experiment, I tried kicking it around with the housemate to try to develop it enough to write. The answer to far too many questions was “I don’t know; that’ll come with character, and I don’t have characters yet.” Trying to force-develop the characters stopped everything cold. I guess I’ll just have to shove this one into the back-brain and hope someone materializes out of the mist to carry it back to me.