Words can mean more than they actually say. In real life, people commonly provide an indirect, implied answer to a question, instead of a direct one—“How do you like your hamburgers?” “I’m a vegetarian.” (implying “…so I don’t eat hamburgers, which means I don’t have a way that I like them.”) People’s actions also have implications and subtext—the grandmother who gives her grandchildren biographies of doctors on every birthday in hopes that they’ll decide to become one, for instance. Even the environment can imply things—toys scattered around a room implies that children are present at least occasionally; a visible layer of dust on the toaster implies that it hasn’t been used recently.

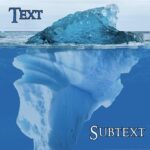

In fiction, subtext and implication convey things that aren’t stated explicitly in the text. The two words get used almost interchangeably sometimes, but subtext is usually a little deeper and more encompassing, and more often relies on the reader knowing or recognizing connections that the characters don’t or can’t see. If the readers know that one of the characters is a veteran assassin, that character’s threatening conversation with a store clerk can have a lot of tense subtext that the clerk, who thinks the assassin is just another tough-talking blowhard, doesn’t see.

Subtext is especially tricky when it involves connections with real-world events that are “outside the book.” Someone unfamiliar with the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s would completely miss the subtext in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible that relates the actual Salem witch trials to the political “witch hunt” that was actively happening when the play was written.

Implication is most common in dialog. Characters, like actual people, don’t always want to say straight out everything they think, know, or feel. There are numerous reasons why a character might want to be indirect—they might find a direct comment embarrassing, or they might not be certain about what they know, or they might want to manipulate someone. They might be afraid of someone overhearing, or stalling to buy time, or reluctant to reveal a personal vulnerability. They might be keeping someone else’s secret, but conflicted about it. They might be in denial about something. They might want to convey a warning or a hint without getting in trouble themselves.

In most stories, there are three possible types of subtext and/or implication:

- The things the writer deliberately puts into the story. This includes much of the stuff that is “shown” rather than “told”—a character’s hunched shoulders and downward look, instead of simply stating “John was ashamed,” or the clues that hint at the murderer’s identity. A large portion of implication in dialog falls into this category, as it is an extremely useful way of conveying the real feelings and beliefs of non-viewpoint characters who are unlikely to say in so many words, “I’m in love with your spouse” or “I think you’re stupid.”

- The subtext and implications that sneak in because of the writer’s culture, worldview, life experience, and underlying assumptions about everything. The writer usually isn’t aware of these, and often readers don’t notice them, either, because they share them…until twenty or fifty years after the story is published, when cultural assumptions have changed. A minor example would be the 1940s space opera in which attendees at a far-future galactic ball still use dance cards.

- The subtext and implications that readers see because of their culture, worldview, life experience, and underlying assumptions about everything. When readers’ worldview is mostly the same as that of authors, this is seldom a problem. When things are changing rapidly, it can cause some serious disconnect. The original Star Trek series got a lot of criticism and pushback because of the diversity of the bridge crew, but also faced criticism because “all the women do is wear mini-skirts and serve coffee to the captain.”

The first sort of subtext and implication are enormously useful in all sorts of fiction, as long as the writer can keep the balance between “too obscure” and “too obvious.” I tend to lean in the direction of deliberately being what I think is “too obvious,” because, as the writer, I know what my characters are thinking, so what is “too obvious” to me is frequently just barely enough for a reader to catch on to why the characters are taking this particular action. I’d rather overcorrect slightly for my own bias than leave my readers bewildered (and inclined to put the book down). This is because, in my stories, most of the subtext and implications involve things that are relevant to my plots or characters, and it is therefore important that my readers catch it.

When it comes to subtext that relies on external connections, I am less worried about readers seeing it and more concerned that the incident or conversation stands on its own—that is, I don’t want something in the story that only works because of the cool subtextual connection to real-life, so that if somebody misses the subtext, the scene seems pointless. I want the scene to stand on its own; ideally, if the reader catches the subtext, then it makes it better, but if they don’t, it’s still a good scene. Mileage varies here. I have known writers whose fiction reflects their overwhelming horror of being too obvious.

Worldview-subtext, whether it’s that of readers or that of the writer, is extremely difficult to do much about. In the case of one’s own worldview, it is often a) extremely difficult to recognize in the moment, and b) practically impossible to avoid without sounding inauthentic and/or doing a poor job. To put it another way, people who have a pessimistic worldview find it difficult to write utopian fiction…and vice versa. About all one can do is try to be self-aware.

The subtext that readers find in work because of their own worldview is not something the writer can, or should, attempt to control. However, comments of this nature shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand, either. There is at least a 50% chance that, if a reader says “You did X thing in this story!” they are pointing at one of the writer’s unconscious biases or worldview subtext, rather than one of their own.

Subtext is incredibly important – to me, anyway. My thoughts on people in power or in leadership positions can be found in most of my fiction, but only (or mostly) in the subtext.

For an example that isn’t about me as a writer, I remember reading the Lord of the Rings for the first time not that long after my father died, very suddenly, when I was still a kid. The scene where Gandalf comes back, with no forewarning, no set-up – all because, I’m sure, in Tolkien’s view, of course someone like that should be resurrected – offended me deeply. My father’s death shaped my worldview profoundly, and Tolkien’s differing view smacked into mine hard.

If one is aware of holding a given view, one may indulge it, throttle it, or try to deliberately invert it in a story. When it comes to inversions, I find it helps greatly (and is often necessary) to presume some sort of technobabble, magic crystals, or alien space bat infestation that makes Policy X a Good Idea in the fictional world, even when I consider Policy X to be a really horrible no good to-be-avoided bad idea in the real world.

One does not have to be a real-world monarchist to write a fantasy story featuring the True Heir to the Throne who is worthy due to an inherent royal nature and divine blessings. For that matter one does not have to be a real-world monarchist to enjoy reading such fantasy stories. The trick, I believe, is to avoid a subtext of “wouldn’t it be great to do things like this here in the real world?”

With respect to the deliberate subtext, my thinking is that in a story with a plot twist, the subtext is has to do double duty. Does that sound right? It has to hold up the top layer story that’s written to lead the reader to an obvious conclusion/ending. But it also must carry along the twist ending. Stated better: the subtext has to be plausible to both the ending the reader expects, and the one the writer writes.

I’ve only written a few plot twist stories so I could be off here. But the hardest part was making sure the subtext elements (spoken but unheard dialog, setting descriptions, small seemingly inconsequential actions) worked for both stories.

Subtext can be fun. Down to the simplest form, which I found in an advice book and have found very useful.

Write down events in the order they occured.

Do not write, John turned when he heard the horn.

Write, when he heard the horn, John turned.

After that, you can start getting into more complex things, like making sentence structure reinforce the relationship of things.

Not really used to thinking about subtext while I’m writing, but I think the WIP may need me to do so.

The protagonist crawls out of a season in a stasis container and notices that she’s physically different than before (fur, claws). This doesn’t seem to bother her much or even register as strange. I am looking for ways to subtly hint that this is not a characterization failure, nor is it numbness due to trauma. She doesn’t know this yet, but the entity that did the physical revisions made corresponding revisions to her body-image, so it all seems much more “normal” than it should.

It’s hard to know how much this needs to be inclued: too little and readers may feel “I don’t believe in this person anymore” or “She is crazy” and too much may just annoy.

I don’t know much about using subtext since I’m an extremely literal person, but the first thing I’d reach for in a situation like that would be a different character who knows the protagonist reacting to her new look for her. I don’t know if that would work for your story, but anytime I as a reader run into a character experiencing something strange and accepting it without comment, I usually expect the author to call it out as strange via different means to subtly let me know they’re aware of how this is coming across and that they have a plan for it.

I unfortunately can’t; she’s alone at this point (her daughters not having hatched yet) except for her alien ally, who is quite useless for this purpose. (Its reaction would always be along the lines of “Honey, you look great!”) Otherwise, a great idea.

She can look back later on and realize that she was manipulated (she realizes that about a lot of things, by and by), but I’m not sure that’s good enough. At some point I think she has to be shown thinking, wow, this should bother me more than it does–and then shrugging it off and going on with her increasingly weird life.