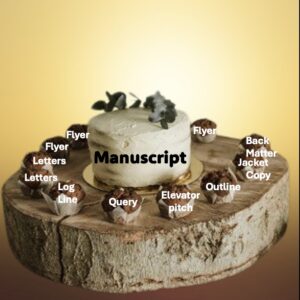

One of the most difficult things I have to do, as a novelist, is to come up with a short version of the book. This is, in large part, because I am a novelist—I have a hard time saying anything in less than 80,000 words—but that’s not my only issue. The rest of my difficulty is because there are so many different types of “short summaries.” Just off the top of my head, there are log lines, outlines, elevator pitches, query letters, back cover copy, and letters-to-reviewers-and-booksellers. Each has different timing, different lengths, and a slightly (or sometimes largely) different purpose. There is no one-size-fits all.

The easiest ones are the primarily process-related summaries, because they are author-specific. (Note that “easiest” does not mean “easy.”) These are the notes/outlines/summaries a particular author happens to need as part of their individual writing process. A total seat-of-the-pants writer probably doesn’t need to start by outlining the plot or characters; some of them don’t even want to take notes on their first draft to try to keep things consistent.

More official, specific summaries crop up during the sales and marketing phases. The first phase is “submitting the book to an agent and/or publisher,” and there are four types of short summaries that an author may want to have at this point, all of them geared toward editors or agents (duh). Spoilers are generally encouraged—editors and agents want to know whether this is a comedy or a tragedy, what the key twists are, who “wins” at the end, etc. (People who are self-publishing probably don’t need most of these, unless they’re useful to their writing process or as a basis for developing summaries for the marketing phase.) In increasing order of length, the summaries one might need during the submission phase are usually:

- The log line. This is a one-sentence summary (and no, connecting an infinite number of clauses with semi-colons so you can make the sentence longer doesn’t count. It’s a one-sentence summary, not a one-sentence-that’s-three-pages-long summary.) It’s the sort of summary you’d find in a TV Guide listing, a teaser sentence with just enough information about who, where, and what the problem is to get someone interested in asking for more. This is what you say at conventions when someone (like an editor or agent) asks what you’re working on. That’s why it’s one sentence. The point is to get the person to ask for more information. Some writers start their pre-writing with a log-line summary and expand it, but that’s totally an optional process thing.

- The elevator pitch. The classic elevator pitch is a little—a very little—longer than a log line. The original idea was that you are on an elevator with an editor, and you have eleven seconds in which to pitch your book before the elevator gets to the editor’s floor and they get off. So maybe a short paragraph. Again, the point is to get the editor/agent interested enough to ask for more information (ideally in the form of a submission). It’s usually easiest to write the log line first, then expand it by a sentence or two to get an elevator pitch. Some people argue for much longer “elevator pitches,” but I go with the original definition, not least because it’s a whole lot easier to memorize eleven seconds worth of teaser than a page or more.

- The query letter. One page that, in theory, gives the editor enough information to decide whether they want to look at the manuscript. Some publishers are okay with a two-page letter, but if their submission guidelines don’t say, leave it at one page. I’ve done whole posts on this topic, but they can be summed up as “a query is not a back blurb.” This is not the place to worry about spoilers.

- The outline. This isn’t the one you wrote as pre-writing; it’s part of a portion-and-outline submission to an editor or agent. So check the publisher/agent’s submission guidelines; some of them want five double-spaced pages, maximum, while others are fine with twenty-five single-spaced pages, and others don’t want one at all). This is the short version of the novel, not the backstory.

The second phase is the marketing phase. The “short summaries” in this phase are all based on the finished and edited manuscript, but they’re each aimed at a slightly different audience, and the idea is to get this reader to decide they like the book enough to buy it. Since they’re marketing, they’re all things that could be useful to a self-published author. They are:

- The back matter and dust jacket copy. This is a one-to-three paragraph teaser, equivalent to a query letter summary but aimed at readers who don’t want spoilers, rather than at editors who do want spoilers. If the book is self-published, the author writes this. If it goes through a traditional publisher, that publisher usually writes both the back matter and the inside dust jacket copy, but sometimes they will ask the author to do it, or offer to let them. If you have strong feelings about doing it yourself, ask, but if they say no, accept it.

- Letter to booksellers and reviewers. A one to two-page letter in which the author talks in general terms about themselves, the process of writing the book, how they got the idea, and very generally about the book (no spoilers), which the publisher then sends out to booksellers and reviewers along with their free review copies. This is a fairly recent invention in the world of marketing books—The Dark Lord’s Daughter was the first time I was ever asked to do it—and I don’t know how much staying power it’s likely to have. I think it’s supposed to provide “human interest” for people in the business, and possibly some anecdotes the recipients can use when they’re hand-selling the book.

- Promotional flyers. A one-page flyer, usually including a picture of the cover/dust jacket, all the basic copyright/bookselling data (like ISBN number, price, publication date, who to contact to get copies, etc.), a bit about the author, blurbs from other authors, and something about the story. This last can either be a whole new summary or just a duplicate of the back cover copy. If it’s new, same principles as for back matter—i.e., no spoilers, just more details about the opening to intrigue readers. Authors can do these on their own, if they have places to give them out (conventions of librarians or teachers, SF conventions, local bookstores, autographings, book fairs…).

I note that the process specific ones are not only specific to authors but may be specific to certain works for authors.

It’s nice to hear I’m not the only person whose reaction to requests for summaries is “If I could have told this story in a few hundred words, I wouldn’t have written a novel!”