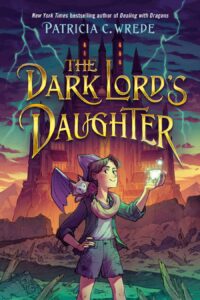

First, the announcements: The Dark Lord’s Daughter has an official release date of September 5! I got my ARCs (Advanced Reading Copies) last week, and it looks very nice. The cover looks like this:

This phase of the publication process was particularly mysterious to me the first couple of times I went through it, so I thought I’d spend today talking about the various stages of getting a book out, particularly the post-writing stage.

What I’m calling the post-writing stage creeps up on you kind of gradually. Writing the first draft and getting it polished for submission is obviously the writing stage. The editing stage comes after somebody has bought the book, and can include major editorial revisions, copy-editing, and line editing. I generally think of this as the second half of “writing the book,” even though how much actual writing is involved can vary widely. Editorial requests are individual to both the editor and the book. I’ve had to add two entire chapters to a book, remove 5,000 words from a 65,000 word manuscript, “pick up the pace,” “make the threat more explicit earlier,” and “this is just a light line edit, everything else is fine.”

Line editing is usually the sentence-level things, and often gets combined with the copy-edit. Line editing involves spotting repeated words, awkward or confusing phrasing, sentences that could be read to mean the opposite of what the writer intended, and so on. Copy-editing is the technical, rules-based stuff: grammar, spelling, syntax, punctuation. “You have used the word “necessary” three times in two paragraphs; can we change one to something else?” is a line-edit question. “According to the Chicago Manual of style, there should be a comma here; should we add?” is a copy-edit query.

I consider galleys and page proofs to be the beginning of the post-writing or production stage, though they can edge back into editing if a lot shows up. “Galleys” were the initial typeset lines, back when type was set by hand, letter by letter. They weren’t divided into pages; they were an intermediate stage between the handwritten (or later, typed) manuscript and the final book. Galleys were proofread to catch any mistakes that crept in during typesetting, places where letters were broken or words incorrectly hyphenated at the ends of lines, and so on. “Page proofs” were the very last stage, when any mistakes that had been made during the initial typesetting were supposed to have been corrected and the resulting lines were divided up into pages.

By the time I started selling, typesetting was done on machines that also divided things into pages, rather than being set by hand, letter-by-letter, and dividing the pages up later. Most of my publishers sent out one final set of typeset pages for me to proofread, which some termed “galleys” and others “page proofs.” So far, I’ve only had one publisher that still involves the author in two rounds of review/proofreading after the manuscript has been typeset.

The page proofs are the last bit that could possibly still be considered part of the writing, if you stretch a bit. What is expected from the author from here out is mainly promotion-related, and again, both the timing and amount varies by publisher.

Usually, around the time you get expected to proofread galleys or page proofs, the editor will ask if there are any writers you’d like to ask for a book blurb. These people go on a list to be sent copies of the book in hopes that they’ll say nice things to put on the ARC or on the cover of the actual book. The publisher doesn’t expect you to be a close personal friend, or even a business acquaintance, of everyone you suggest, but they don’t expect you to give them a list of your cousins and college classmates, either.

Cover art and book design is happening behind the scenes at this point. I say “behind the scenes” because out of twenty-some books, I’ve gotten to see early stage cover sketches about three or four times. Usually, by the time I see the cover, it’s too late to change anything. On one book, the editor very apologetically asked if I could alter a character description to fit the cover, because it was easier to change two lines of type than the particular type of painting the artist had used. (It was a brilliant cover, so I didn’t mind at all.) Book design, I get to see when the page proofs come.

Six to eight months before the book hits the stores, the Advance Reading Copies get printed. Publishers used to send a flood of them to reviewers, chain store buyers, and anyone else they could think of, but these days, a lot of those people prefer to get electronic copies that won’t fill up their basement. At this point, planning for promotions and publicity starts showing up on the writer’s radar.

Again, a lot of the planning has already been done at the publisher’s level—they have a system, and they probably won’t give you chapter and verse on it unless you ask your editor for specifics. How much they do for your particular title depends on where it falls on their list. What they do can range from the basic “send out copies for blurbs and reviews” to a full-blown book tour. Most of what the publisher does is invisible to most writers, because unless a book is a lead title, the publisher is doing stuff to sell it to bookstores and libraries, rather than to readers. Most writers don’t read trade publications aimed at booksellers, book distributors, or librarians, so they aren’t going to see or hear about ads and book reviews that appear in those publications. This can lead the writers to think that their publisher is doing nothing at all.

On-line publicity, on the other hand, is usually aimed at readers. Some publishers leave on-line marketing entirely to authors; some will at least make suggestions or give advice, and some have their own blogs, email newsletters, and official social media presence. Most publishers expect their writers to have some on-line presence (an author web page is a pretty standard minimum) and to do some on-line promotion on their own, but so far, nothing has turned up in any contracts I’ve seen that would spell out exactly what expectations are.

That is such a lovely book cover.

“Line editing involves spotting repeated words…”

I initially read that as a word repeated twice where only once was meant (“Kim sensed the the sharp-edged magic”) and thought “wouldn’t deleting the extra word be copy-editing, rather than line editing?”

“After months of futile attempts to produce a cover design and of damaging the text by subjecting it to the expert attention of copy-editors, a proof rich in imported error would emerge accompanied by an unapologetic note requiring its return corrected by first light the following morning.” [The Biographer’s Moustache]

―Kingsley Amis

I read the post title, and immediately thought, “Oh, yes, the part where I’ve finished the story and am sending it out to be ignored by as many people as possible!” 😉 I’m looking forward to when I default to this definition of “prepublication” instead; thanks for the insider view!

That is a very fun cover. I can’t wait to both read it myself and start pimping it to people at my library. 🙂

O frabjous day!

Ooh, an official release date and a cover! Can’t wait!

I’ve just ordered the book.

I know a bookstore that has a basement full of advance reading copies. I bought one of comic strips and it was black and white only.

I worked for a company whose product was reports (on pension plans). My boss always had someone else read the reports because he’d written it and when he read it, he read what he’d written.