Most of the time, people analyze story structure as a chain of actions and the consequences of those actions, leading to an eventual climax. While that’s true for a lot of writing, it ignores a critical factor that is so obvious and necessary that I, like many writers, do it automatically without thinking about it.

Choice.

Every character in every situation has at least one choice: whether to act, or not. Usually, there’s more than one possible action as well. Each choice has consequences for the character (and, inevitably, for the story).

Sometimes, the consequences of one course of action are so clearly dire that the preferred choice is obvious—run from the forest fire vs. stay where you are is usually a no-brainer. Sometimes, the choice of action appears trivial or inconsequential to the character at the time—whether to go to a movie or to that new café, for instance.

Whatever action the character takes will have consequences. At the start of my novels (and, indeed, most novels), the protagonist usually doesn’t have the information (or, sometimes, the agency) to accurately predict what the real consequences of their actions will be (especially the ones that seem trivial). This is how taking over an estate from one’s retiring uncle leads to spending a year hiking across dangerous mountains to drop a ring in a volcano. It’s how buying a couple of cheap robots from some nomadic traders leads to one’s farm and family getting blown up by the Empire (and, later, to the overthrow of said Empire and the return of the Jedi order).

At any point in a story, the characters always have the choice not to proceed further along the author’s preferred plotline. This choice always has consequences. Sometimes, the consequences of choosing an action are obviously unsatisfactory—“the character will die.” Other times, the consequences of abandoning the plot look favorable—“the character will go home to a normal, safe life until he/she dies of old age.”

The catch is that “I’ll go home and live a boring life” is only the sensible choice if the boring life is the actual consequence of dropping the investigation and going home. The character can’t be certain of that. They can assume that abandoning the search or investigation or quest will lead to a normal, boring life, but the actual consequences may be that the villain decides that the character won’t be missed (since they have officially abandoned the quest), and can therefore safely be kidnapped or killed. Or the actual consequences may be that because the team that remains on the job doesn’t have the main character’s perspective, they don’t get anywhere, the villain wins, and the character has to cope with living in the world that results.

The authors have two main ways to cope with this issue. First, the author can pick a main character who won’t give up, walk away, drop out, etc. If Jackie is consistently reckless or impulsive when she gets angry, then it’s believable when she dashes headlong into a situation without thinking. If Marco gets obsessive about making small things fair, it’s believable that he won’t give up as long as he thinks something unjust is happening. If Ivan is beyond stubborn, he won’t walk away from whatever he’s committed to, even if it would be more sensible.

Second, the author can choose the actual consequences of the supposedly “sensible” choice—the circumstances and consequences that the character didn’t know or expect, that make walking away from the problem the worst choice, not the safer one. In other words, the “sensible” choice has consequences, that lead to the character getting more involved in the problem they thought they were walking away from. The villain thinks “walking away” is a trick and kidnaps the character (or a family member or love interest). Rumors start up that the character has been bribed to walk away, which will ruin his/her career. A friend tries to do the job the character is walking away from and is injured or killed, making the character feel guilty and responsible.

In some cases, the author can get the character to stick to the plot by forcing them to consider the down side of abandoning their quest. Having other characters point out possible negative consequences, or persuade the protagonist to stick around “at least til we finish this bit” can also work to either change the protagonist’s mind or to keep them on track until they reach the point where the obvious consequences of non-action have become dire (“if you leave now, everybody will die/the world will end/etc.”).

Occasionally, the character succeeds in stubbornly avoiding the intended plot (they don’t kill the dragon, catch the spy, save the ranch, etc.), and by the time the consequences come around, it’s too late to fix—the dragon has burned down the village, the spy has sabotaged the weapons factory, the bank has foreclosed on the ranch and sold it to the railroad, etc. Authors who are wedded to their original plot tend to either give up at this point, or else turn their story into a tragedy or cautionary tale (which can work amazingly well). There is, however, another alternative: write the story of the protagonist having to cope with the results of his/her actions or non-actions (which frequently means starting over in some way—rebuilding the village, coming up with a new defense plan [or rebuilding the factory in a big hurry], finding a new job instead of ranching).

The choice is the author’s.

The trouble I frequently encounter is one where the character “giving up” seems to be the best choice not just for the character personally but for having the task succeed – let the official authorities and qualified experts deal with it. “I’d just get in the way, destroy clues, and so allow the murderer to get away. So I’ll let the police handle the murder investigation and keep myself clear.”

Instead of being the Hero Who Slays the Dragon, the character is more like the King who offers half his kingdom and the hand of his daughter in marriage – only without even the kingdom or the daughter.

This seems to be a mismatch between character and plot. If the problem is the authority’s responsibility to solve, and they can do so, then the main character should probably be an agent of the authority. Then it is clear why they are tackling the problem: it’s their job.

If that’s not satisfactory, there are options:

–The authorities are corrupt and won’t solve the problem, so the protagonist has to do it.

–The protagonist has knowledge or capabilities which the authorities lack, making them a better choice.

–The side effects of the authority’s solution are intolerable, so a different one needs to be found. (They will deal with the bug infestation by nuking the planet from orbit, but we are on it….)

–The situation is an emergency and there is no time to get the authorities involved.

–The protagonist has such a bad relationship with the authorities that they’re unable to enlist them without personal disaster.

Roleplaying games often fall into the problem you describe. The PCs are not reasonable people to be tackling the problem, but somehow they do so anyway. I’ve long since lost patience with this as player or GM.

It’s not necessarily a case of Authorized Authorities but instead can be a case of someone competent enough to be a reasonable choice to tackle the job. If my main character is (and believes he is) competent enough, he’s a lot less likely to balk, especially if circumstances make it a case of “it’s personal.”

If Princess Mary decides her little lambing experience is enough to have her shear the Black Sheep of Aaaagh herself, rather than having her father the King put out a call for a professional shepherd, then well and good. But if the princess decides that a DIY shearing is beyond her competence here, then either some excuse is ginned up as to why she has to try anyway, or else the main character becomes The Shepherd Hero, with the princess being reduced to the status of a standard hero’s reward.

When my characters balk, the usual reason is that they decide rightly that DIY plot engagement is a bad idea, rather than quitting for “wrong” reasons like laziness, selfishness, greed, etc.

(Hmm. Just got hit with an idea where Princess Mary takes on the sheep-eating dragon herself despite her doubts because she *really* does not want to become a standard hero’s reward.)

I would read a book about a princess who chose to save her kingdom herself to avoid being some hero’s bride!

If the protagonist has the option at any point in the story of abandoning the quest (or whatever) but does not, an important question needs to be answered: What binds them to the plot? Too much mediocre fiction overlooks this point, at best offering up the lame answer “Because they’re the hero.” There has to be a compelling reason that they persist—in other words, they really do not have a choice.

I like this article; it was interesting to look at part 1 of my WIP in this light.

The protag starts off tackling the problem because it’s her job, and because she failed on a similar problem in the past and is motivated to show she can do better. It doesn’t look like a very big problem at this point.

Things escalate and her boss offers her a stark choice: get co-opted by the military and go on the lam. She feels utterly unprepared to go on the lam, so she goes along reluctantly with the military plan.

Things escalate much more and she realizes her remaining choices are to be taken by the alien bugs, or die. Dying is probably the morally correct choice but she really doesn’t want to die.

It’s a series of choke-points where her choices are suddenly far narrower than she expected or wanted. Then Part 2 reverses the structure: she starts out thinking she has only mundane day-to-day decisions to make, and ends up realizing she actually has agency.

I didn’t see this parallelism; now that I do maybe I can point it up more.

Rising tension is often the cutting off of choices and/or the increased cost of choices.

I’ve never had a problem with my characters’ agency. They make their own choices as they please. The problem I have is figuring out how to tweak the plot so their use of agency still leads to the end result I’m looking for.

For example, the moment I realized that my runaway princess would reasonably know one or two of the royal guards passing through town, I started working with their captain’s character and he immediately interfered with the plot by finding my MC and hauling her in the exact opposite direction I needed her to go. I still haven’t worked out the root issue of this, which is that his character feels duty-bound to do as the King Regent asks (as he is unaware that the King Regent is secretly usurping the throne). Between the KR’s propaganda about the runaway princess being helpless and distraught and the fact that she is very unkempt when the captain finds her, he has no real reason to take her word over the KR’s. My princess may need to use her more-recently-acquired thieving skills to escape, because I don’t see the captain becoming an ally until *after* the King Regent has been discredited. The trick then is getting her moving in the right direction, since she doesn’t know she has potential allies hidden in the Northern mountains yet…

Oh, the joys of working out plot points so they work in plausible sequence. 🙂

A few other ways around this problem:

– No choice. Have your protagonist under a geas, or with a chip in their head. They really don’t have a choice.

– Other choices are a nightmare. “Nice family you got there, pal. Be a shame if anything happened to them.” Or the secret police show up, and explain just what will happen if they don’t undertake this task.

– Not that kind of protagonist. Make it clear your protagonist isn’t the kind of person who lets others risk their lives to do something dangerous. Make them duty-driven, or feeling guilt, or they’re a daredevil. (My just finished drafting the third novel in a trilogy, and one of the protagonist’s major traits is he’s everybody’s older brother. He’ll always step up.)

– The plot takes a hard left turn. Have your protagonist refuse. Next chapter, kill them. Have someone else react to the killing, and step in to be the protagonist. Your readers won’t likely see that one coming.

Considering that I as the writer probably wouldn’t see that last one coming, I’d be surprised if the readers did. 🙂

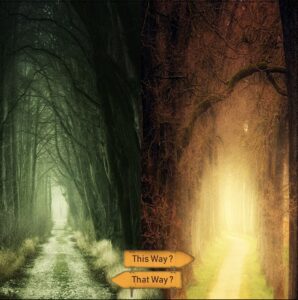

As an aside, I like that the icon this week is green vs golden and so doesn’t hit you over the head with an anvil about the obvious right and wrong choice.

“More than any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.”

—Woody Allen