For many readers, one of the more effective ways of describing a scene is through the viewpoint character. The technique is a sub-category of “description as seasoning,” which I talked about last post, but it’s hard to describe in a brief paragraph. Hence this post.

For many readers, one of the more effective ways of describing a scene is through the viewpoint character. The technique is a sub-category of “description as seasoning,” which I talked about last post, but it’s hard to describe in a brief paragraph. Hence this post.

The first thing is that, when most people enter a room or a park, they see the whole thing…but they don’t register everything, much less remember what they see. When I drive down a new street, I see the whole street, but I could not tell you the color of the second house on the right without checking…unless it was unusual in some way (painted in stripes, or neon green when all the other houses were neutrals, or had a full-sized mural on the front).

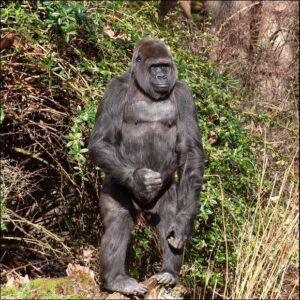

This is how most people work. There is so much data available when people look around themselves that our brains are programmed to ignore most of it unless it is 1) a possible threat (moving, unfamiliar, large), 2) unusual, different, or unexpected (e.g. an elephant walking through a supermarket), 3) congruent with the viewer’s focus (as with the selective attention video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo ) or personal interests. Realistic characters, unless they have reasons to be hyper-aware, aren’t going to work any differently. They’re going to register things according to how relevant they are to that character, starting with anything threatening, different, or interesting.

The second thing is that, when people enter a new place, they do a lot more than look at it. I tried to go to a new restaurant this weekend, and the first thing that I registered when I walked in the door was the thumping bass beat of the much-too-loud music. I left. I couldn’t describe anything else about it in detail without going back to check deliberately. When I walk into someone’s house—especially if I’ve been there before—I might notice if something major has changed. I will definitely notice if I smell bread or cookies baking, or if something smells musty or burnt. I might notice if the person is using potpourri or air freshener, but I don’t tend to register that unless it’s rather strong—for me, that’s more of a subliminal effect. When I come into a building from outside, I register temperature changes, especially pleasant and unpleasant ones—“Why is the air conditioning turned up so high?”

When a viewpoint character enters a place, they aren’t just seeing it. They’re experiencing it, and they register different parts of the experience as they become more personally relevant. If I walk into my sister’s house when it’s bitterly cold and windy out, the first thing I register is that it’s nice and warm. I’ll notice the smell of the curry next, and only then realize that she’s rearranged the furniture (and if the furniture is where I expect it to be, I won’t notice it at all unless there’s stuff piled in the chair where I usually sit). On a similar day, if I’m really hungry when I get there, I’ll notice the curry-smell first, and the warmth second.

That’s what I mean when I talk about description through character: describing things as the characters experience them, particularly the viewpoint character. The viewpoint character allows more internal reactions and sensations (“The doorknob felt rough. She let go hastily, brushing rust from her hand”), but you can also have a non-viewpoint character enter a room, sniff, and say, “Curry for dinner again?” or “Smells like something died under the refrigerator.” Characters who are already familiar with a place can comment on things that have changed—“When did you cut down that big oak?” “You finally got a writing desk.” All of these give you a two-fer—the reader gets a bigger picture of the place in which the scene is happening, while also getting some information about the character. Sometimes, you get a three- or even four-fer—descriptive details, characterization of the speaker, plus more details and characterization of the POV character through their internal reaction to what the non-POV says or does.

Stage business works similarly to dialog and character reactions. The viewpoint character may not register anything but “it’s a flower garden” until a secondary character starts sneezing because they’re allergic to goldenrod, or somebody else tries to pick the rugosa roses and gets stabbed by their many, many thorns. The viewpoint character may not know that those are antique side tables until they try to set a teacup down on one and the host pitches a fit about possible damage to the finish. The viewpoint character can watch other people making a close examination of something—a dent in a car door, a portrait, the pattern in a rug or curtain, a pile of tools left out by the back door—that didn’t mean anything to the POV until somebody else displayed interest. And the POV character’s reaction will provide yet more information, whether it’s “Why is he peering at that thing,” “Isn’t that just like Suli, fussing about china patterns,” or “OMG, that shovel Ivan picked up has blood on it!”

The main problem with this style of description is that the writer has to pay attention. A tough-guy character who rarely says anything other than “yup” or “nope” isn’t likely to comment—verbally or mentally—that the cerulean-and-cream brocade curtains remind him of the Greek Key china his Aunt Sophia brought with her when she emigrated forty-two years ago. Not unless the character has consistently made similar mental comments right from the start of the story (if he’s been doing this verbally, he’s clearly not a yup-or-nope kind of guy). And not only does the character have to be a person who would notice the curtains and connect them to a family memory, he has to be someone who would call them cerulean-and-cream instead of blue and white, and refer specifically to a Greek Key pattern, rather than “the geometric border on the fancy dinnerware.”

In other words, word choice becomes even more important, because it not only has to convey some objective physical characteristics of the place or object or person being described, it also has to do so the way the particular character would say/think/notice it. This makes it a poor choice for writers who like ornate descriptions such as “the freshness of morning breathed and shimmered in that lofty chamber, chasing the blue and dusky shades of departed night to the corners and recesses,” unless they can actually write a character who talks and thinks like that all the time.

(and if the furniture is where I expect it to be, I won’t notice it at all unless there’s stuff piled in the chair where I usually sit)

This was my problem with a lot of character physical description — if the people in her life look like they always do, the POV character isn’t going to think about what they look like. I’ve gotten better at working it in anyway, but it’s still a struggle.

Also, I now have a strong desire to write a taciturn tough guy who has a running mental commentary about the interior design of all the places he goes. 😉

Can you introduce some changes that the POV character is just now noticing? Hey, Jenny dyed her hair. I hadn’t realized just how lined Paul’s face was becoming until I saw him in the sun. Carl’s new wardrobe makes him look like a stuffed suit–wonder why he needs to fit in like that? Molly seems to have grown an inch in the last month, and the new earrings are probably meant to make her look grown up but they’re just so tween.

At least it’s better than trying to describe the protagonist in first or tight-third. We find out that my protag has black hair (though I suppose you could guess from her name, which is ethnic Indian) in part 2, where she wakes up to find she’s covered in black fur and notes it’s the same color her hair had been. A bit late, if you ask me, but I can’t get it in earlier.

If those changes actually happen in the story, sure, but then the people wouldn’t look like they always do, and then the POV character would notice the changes, and I wouldn’t have a problem describing them. I can’t just arbitrarily paste changes onto characters so that I’ll have something to describe.

Describing the POV character is a particular kind of hell, yes.

Is it late? If the character is signaled as ethnic Indian (either Old or New World) then straight black hair is the default to be presumed unless specified otherwise.

On the other hand, if you’re doing the thing where names are highly unreliable as indicators of appearance, because of the future setting, or for some other reason, then maybe it is a bit late.

I once was annoyed with a journey through wilderness by two warriors.

They were traveling together for safety, and there was no description of the scene, not even whether there were defensible places, or points of danger for ambushes.

It isn’t always appropriate, but the protagonist is often the least described character, supposedly allowing more readers to identify with them.

Whatever description there is needs to come early, as the reader will create a firm mental image, even lacking basic clues. There are few things as disconcerting as picturing someone tall with dark, wavy hair only to be told two pages later that they are short and blond with tight curls.

Definitely. I once read a middle-grade fantasy novel about which I remember almost nothing except that the protagonist’s wizard mentor didn’t get a physical description until the climactic scene, at which point I discovered he was a lot younger than I’d been picturing.

Not just viewpoint characters though, antagonists too, if only in dialog:

“Look at him! Faded denims. Scuffed leather jacket. Anyone can see he is mired in poverty, unimportant, irrelevant, and worth ignoring.”

“Of course I’m comfortable with straight lines. But I prefer my architecture to be sexy, to have the kind of shape that stimulates me -”

Yuck. That was more effective than I thought it would be.