“Writing forsoothly” is a term that has floated around the publishing industry for decades, resurfacing every time a novel that uses elevated or pseudo-historical language becomes popular, and a zillion people decide to imitate it. It’s easiest to see in dialog, when the author clearly has no idea that there’s a difference between when you use “thee” and when you use “thou” (let alone no notion of the social conventions around using “thou” versus the singular “you”), or that verb forms don’t just add -est or -eth to the end at random. Once in a while, though, forsoothly phrasing turns up in narrative, especially description, and that’s what I’m going to talk about today.

The first thing a writer has to keep in mind is that the more forsoothly the prose, the more difficult it will be for most readers to parse. I adore William Morris’s fantasies, but in order to read or re-read his work, I have to get into a mental space where descriptions like this are normal and easy to parse:

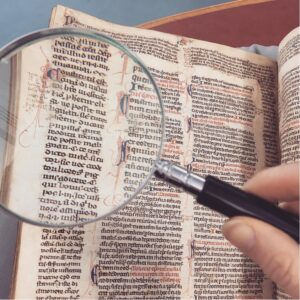

“Now he stood in the door of his house, which was new and goodly, sniffing the sweet scents which the morning wind bore into the town; he was clad in a goodly long gown of grey welted with silver, of thin cloth meet for the summer-tide: for little he wrought with his hands, but much with his tongue; he was a man of forty summers, ruddy-faced and black-bearded, and he was called Clement Chapman…Therewith the carle led him into the house; and if it were goodly without, within it was better. For there was a fair chamber panelled with wainscot well carven, and a cupboard of no sorry vessels of silver and latten: the chairs and stools as fair as might be; no king’s might be better: the windows were glazed, and there were flowers and knots and posies in them; and the bed was hung with goodly web from over sea such as the soldan useth. Also, whereas the chapman’s ware-bowers were hard by the chamber, there was a pleasant mingled smell therefrom floating about.” –From The Well at the World’s End by William Morris https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/169/pg169-images.html#chap0102

Morris is writing in a pseudo-medieval style that he adapted from medieval epics and romances. He’s hard for modern readers to read because he’s using both archaic word choices (carle, goodly, chapman) and unfamiliar syntax and sentence rhythms (at great length the sentences backwards run). It’s not as hard as reading The Canterbury Tales in the original, but the reader still has to pay close attention until they get a handle on it. E. R. Eddison is somewhat more accessible, because he chose a pseudo-Jacobean style, which is more recent. (See his The Worm Ouroboros https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/67090/pg67090-images.html; I’m not going to quote it here). J. R. R. Tolkien also used a lot of elevated language, but he wasn’t trying to emulate medieval or Elizabeth style verbatim, which makes his work more readable (and more popular) than the other two.

All three of these writers knew exactly what they were doing with their language. They were imitating and recreating the language and style of earlier times, but their sources were works like the Norse sagas, medieval poems, Shakespeare, Arthurian legends, Restoration literature, Virgil and Homer, etc. Any copy-machine effect was minimal, or possibly a deliberate choice to achieve an effect they wanted enough that they were okay with not being perfectly accurate.

The specific techniques they used are applicable to any fiction: careful word choice, attention to the rhythm of the words, syntax that is both complex and consistent throughout the novels. These effects are amplified by the fact that these authors frequently use the block-of-description method. Since there’s often little or no plot or characterization in these descriptive passages, other things have to hold the reader’s interest or attention—the necessity of parsing unfamiliar words and unusual sentence structure, the gorgeousness of whatever is being described, or, in some cases, the gorgeousness of the sentences themselves.

A few tips in a blog post aren’t going to help those people who think that writing forsoothly sounds really cool, but who don’t have the time or interest in doing the work to create something that works for them. Because the very first and most important “tip” is to learn the actual historical basics of whatever sort of language you want to use. Learn the actual verb conjugations instead of just sticking “-eth” on the end of everything. Learn the proper forms and usage of archaic pronouns, if you’re going to use them (I cringe every time a character says something like “Thine belt beeth unfasteneth,” which gets everything wrong in one sentence of dialog). And in my experience, it isn’t enough to look things up on the internet unless you are willing to go through a really painful, sentence-by-sentence copyedit of the finished manuscript.

Your best bet for getting the language right, especially if you’re going for usage in dialog, is to read plays and/or poems written at the time and place you want to emulate. Read them out loud. Shakespeare is good for Elizabethan English, Marlowe and other Jacobean playwrites are good for that usage. Le Morte d’Arthur and The Canterbury Tales are good for Middle English; much earlier than that, and you’re looking at translation more that simply archaic language. Translations of Icelandic and Norse sagas and eddas have a rhythm that comes through in good translations.

And from all of these, you can pick up familiar words that are used in unfamiliar ways that are still easy to pick up from context (a goodly man, to worry at a bone), words that have fallen out of common usage but are similarly understandable (therewith, whereas, therefrom, forsooth), and unfamiliar words that may or may not be clear in context (carle, girdlestead, eyot). These can be used sparingly, for flavor, or they can entirely replace modern terms; just keep in mind that Morris and Eddison, who use a lot of archaic language, are far less accessible to readers than Tolkein, who depends more on formal language and syntax than on archaic vocabulary to achieve his effects.

Marie Brennan has a great post about people who do the same thing with Latin: they try to get the ‘look’ of the language right without having the first clue how the grammar works, and anyone who does know finds themselves metaphorically bleeding from the eyeballs.

https://www.swantower.com/essays/writing-craft/pleaser-dont-doed-thising/

On the other hand, when it’s done well, forsoothly language is an excellent way to provide fantasy immersion and really lovely prose. I’d add The Ill-Made Mute by Cecilia Dart-Thornton as another example of someone getting it very right.

I love “writing forsoothly” as a description for this kind of prose! I first came across it in The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey, and it’s stuck in my head ever since.

“Among all other lessons this should first be learned, that wee never affect any straunge ynkehorne termes, but to speake as is commonly received: neither seeking to be over fine nor yet living over-carelesse, using our speeche as most men doe, and ordering our wittes as the fewest have done. Some seeke so far for outlandish English, that they forget altogether their mothers language.”

—Arte of Rhetorique (1553), Thomas Wilson

Lord Dunsany seldom used actually archaic terms, though he could put some interesting loop-de-loops in sentence structure

Lots of fun ways to give some flavor to language. In my first (and probably most ambitious) novel, I had a city where everyone the protagonists encountered spoke in 15th-16th century thieves’ cant – or as close to that as I could get.

One character came from a parallel world where Rome hadn’t influenced northern Europe as much, including the Angles and Saxons. I eliminated – I mean, took out – all the Latin-derived words from her dialog.

Good(ly) times.